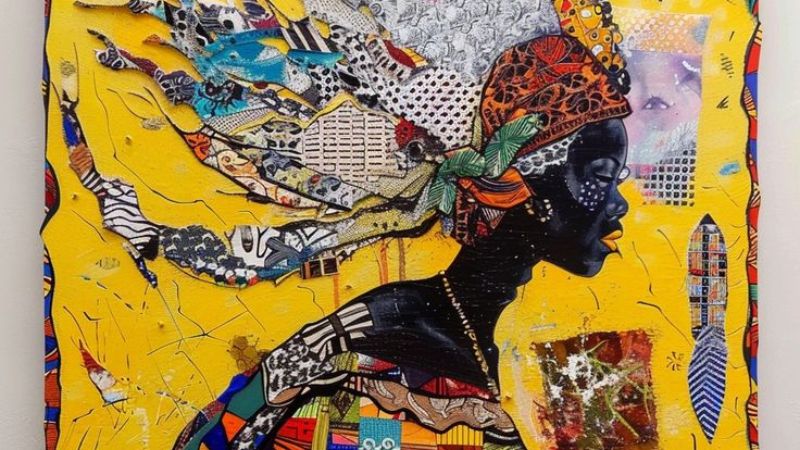

African Modernism in art emerged during the mid-20th century as a powerful response to colonial domination and a bold effort to reclaim African cultural identity.

Unlike Western modernism which often drew inspiration from African forms without acknowledging colonial realities, African modernism blended traditional aesthetics with modernist techniques to assert political independence, cultural pride, and nationalism.

Artists from across the continent redefined modernism, using it not as imitation but as transformation rooted in local histories, symbols, and struggles.

Modernism in African Art | When Did It Take Place?

African art’s modernism emerged in reaction to Western ideas of modernism, which frequently ignored colonialism, imperialism, and the African experience.

European modernism often dismissed the colonization and oppression of African societies during this time, even as it celebrated breaking with tradition and exploring with new forms.

Ironically, despite the removal of African voices from the history of art, Western artists such as Picasso were influenced by African art.

However, artists in the diaspora created a distinct and politically charged visual language by fusing Western techniques with African traditions, which led to the development of African modernism.

Inspired by groups such as Pan-Africanism, artists such as Ernest Mancoba and Skunder Boghossian employed African symbolism and abstract to proclaim cultural independence and challenge Western dominance.

As several African countries gained independence by the middle of the 20th century, particularly between 1957 and 1962, modernist art grew into a tool for establishing new cultural and national identities.

Through their boldly emotional paintings of urban life and unfairness, artists such as Dumile Feni and Gerard Sekoto used their art to draw attention to the hardships under colonial rule and apartheid.

Although their art was grounded in African reality, it challenged a belief that modernism was only a Western event by interacting with global modernist trends.

Understanding Africa’s cultural richness and how its artists employed modern tools to recover their legacy, fight oppression, and add to the larger canon of world art is essential to comprehending African modernism.

Overview of African Modernism Artwork

In reaction to colonialism and the fight for African independence and cultural identity, African modernism became a powerful artistic movement.

African artists used modern art to oppose colonial stereotypes starting in the late 19th century and gaining popularity throughout the rebellions for independence of the 1950s and 1960s.

In order to show their creative intelligence, many early modernists studied in Europe and turned to realism. They showed African elites, common people, and historic figures to foster a sense of pride.

In order to convey a revived feeling of identity and cultural power, artists like Ibrahim El-Salahi and Uche Okeke started fusing traditional African aesthetics with modern methods as ideologies like Pan-Africanism and Negritude gained traction.

However, because of political and economic unrest, African modernism’s momentum began to decline by the late 1960s. Some painters sought originality by rejecting both African culture and Western influence, while others allied with global modern art.

A more diverse art the environment resulted from these diverse approaches, opening the door for modern African art in the 1970s that was less national and more international in outlook.

African modernism, which was formerly disregarded in the history of art worldwide, has been recognized as a significant period in Africa’s cultural and political development, showing how art evolved into a means of regaining identity and rewriting stories.

Themes of African Modernism Artwork

| Themes | Description |

| Decolonization | African modernism was deeply connected to the liberation movements against European imperialism. |

| Identity | Artists reasserted African cultural pride, nationalism, and personal expression through their work. |

| Hybridity | African modernism transformed European modernism by incorporating local symbols, history, and struggles. |

| Decline and Transition | By the 1970s, African modernism transitioned to contemporary African art, which became more global and less focused on nationalism. |

Regional Survey

(i) Northern Africa

The northern part of Africa has been interacting with its neighbors across the Mediterranean since the time of ancient Egypt, but European powers’ colonial projects, starting with Napoleon’s conquest of Egypt in 1798–1801, have greatly influenced its modern history.

In order to carry out his grand plan to modernize Egypt, Muhammad Ali Pasha, who took power in 1805, enlisted French engineers, architects, investigators, and researchers, many of whom had traveled with Napoleon. The fine arts also showed this immigration of European expertise.

Some of the most well-known Romantic painters in Europe, including Charles Gleyre, Jean-Léon Gérôme, Eugène Delacroix, Emile Vernet-Lecomte, and David Roberts, went to Egypt and other parts of North Africa in search of exotic, Oriental subjects.

Some even made their homes in places like Cairo, where they imported European art forms like Post-Impress and Romanticism. European artists dominated North African artwork and sculpture by the early 20th century.

They established clubs, art schools, and French-style salons to draw in an elite class that saw such support as a mark of rank.

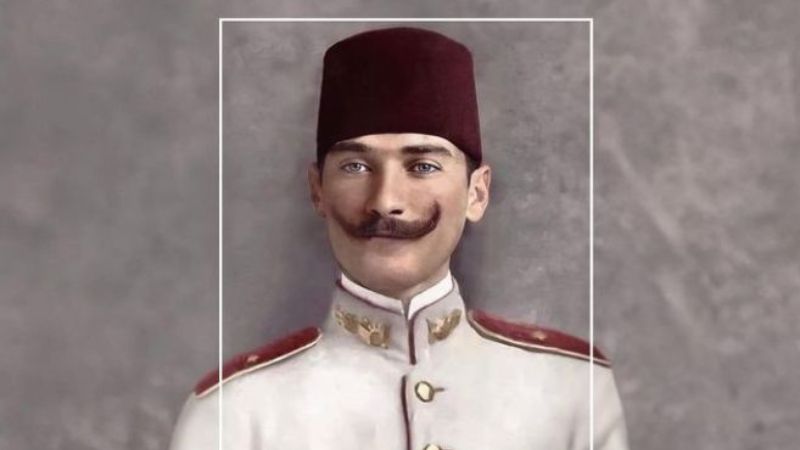

But the nationalist movement led by Mustafa Kamil Pasha, the founder of the Egyptian National Party, soon challenged European domination.

In 1908, art patron Prince Yusef Kamal founded the School of Fine Arts in Cairo as a result of his drive for a modern, independent Egypt that placed a strong emphasis on secular education.

With graduates including Mohammed Naghi, Youssef Kamel, Mahmud Mukhtar, and Raghib Ayyad—Egypt’s earliest modern artists—this school signaled the beginning of modern Egyptian art.

Mahmud Mukhtar was notable among them for being an early leader in the field of neo-Pharaonism, which brought back ancient Egyptian themes.

Given how alien Western forms like Post-Impress and Orientalism felt, he saw this as a means of conveying modern Egyptian identity and nationality.

His famous carving, Egyptian Awake (1919–28), which included an awakening sphinx and a peasant lady, was the pinnacle of the neo-Pharaonic movement and captured the essence of Egypt’s nationalist movement.

La Chimère, a group founded in 1927 by Mukhtar and colleagues like Ayyad and Naghi, rejected Orientalist naturalism and portrayed Egyptian folklore and rural life using Expressionist methods.

They supported political nationalism and saw the common people as the nation’s essence, even though not all of them subscribed to neo-Pharaonism.

In the 1920s and 1930s, modern Egyptian painters were exposed to European art movements with the backing of the state.

The Art and Freedom organization, founded in 1938 by author Georges Hunain, released the manifesto For a Liberation Independent Art following the rise of Fascism in Germany.

They opposed nationalist styles and supported individual artistic freedom, rejecting groups like as La Chimère and the state-sponsored Society of Art Lovers, which operated the powerful Salon du

Hussein Youssef Amin, on the other hand, promoted a distinctively Egyptian art that was based on Pharaonic, Coptic, Arab, and folk traditions when he created the Contemporary Art Group in 1944.

Despite being influenced by Cézanne, Amin’s group’s artwork criticized the ruling class and governmental systems while highlighting social issues including poverty and portraying rural Egyptian life.

Elitism and European avant-garde styles were also rejected by the Group of Modern Art, which was founded in 1947 at the Institute of Pedagogy in Cairo.

Following the 1952 Revolution, the group adopted revolutionary nationalism under the leadership of artists such as Gamal al-Sigini, Hamed Oweis, and Gazbia Sirry.

They aligned their modernism with Nasser’s political philosophies of Pan-Africanism and Pan-Arabism by fusing social realism with Coptic and Egyptian folk themes.

Since Delacroix’s visit in 1832, French artists have introduced and preserved Orientalist painting traditions in Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco.

Before independence movements in the 1940s encouraged indigenous artists to reject these colonial aesthetics, French-style art schools predominated.

French-Tunisian artist Pierre Boucherle established the School of Tunis in Tunisia. Although the group did not promote a particular style, its leader, Yahia Turki, backed the usage of Tunisian folk visual culture.

Rather, they depicted contemporary Tunisian life and national identity using realist means. Finding genuine modern trends became more important after Tunisia attained independence in 1956.

Younger artists were inspired to experiment with a peculiarly Tunisian-Arab modernist style by the adoption of Abstract Expressionism by influential artist Hedi Turki.

Nja Mahdaoui produced lyrical abstract compositions with calligraphy influences, whereas Najib Belkhodja established a hard-edge abstract style influenced by Medina architecture and square Kufic calligraphy.

Despite having daring styles, they were not very popular, but they did highlight Tunisia’s contribution to calligraphic modernism.

Finding true modern trends became more important after Tunisia attained freedom in 1956. Younger artists were encouraged to experiment with an uniquely Tunisian-Arab modernist style by the adoption of Abstract Expressionism by influential artist Hedi Turki.

Nja Mahdaoui produced lyrical abstract compositions with calligraphy influences, whereas Najib Belkhodja established a hard-edge abstract style influenced by Medina architecture and square Kufic calligraphy.

Despite having daring styles, they were not very popular, but they did highlight Tunisia’s contribution to calligraphic modernism.

European painters brought the Orientalist and Parisian modernist styles to Morocco, just as they did in Tunisia and Egypt.

However, politically conscious indigenous painters began to appear around 1956, the year of Moroccan independence, with the establishment of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Casablanca (1950) and the Escuela de Bellas Artes in Tetouan (1945).

(ii) West Africa

Following European forces’ colonization of West Africa in the late 19th century, modern art made its way there, much like it did in the Sudan.

Early local painters had no direct Western models to emulate or confront because there were no professional European artists living in West Africa at the time.

Aina Onabolu (1882–1963), a Nigerian portrait painter, was the first artist from West Africa to adopt Western painting techniques.

Onabolu made the case in his 1920 booklet A Discourse of Art that the academic traditions of British artists from the 18th century, such as Joshua Reynolds, could serve as the foundation for contemporary African art.

He thought that this scholarly approach would dispel racist notions of African inferiority and give the African elite a potent platform to showcase their uniqueness and modernity.

His sensitive and in-depth depictions of contemporary Africans were hailed as examples of creative nationalism.

In contrast to colonial art instructors like Kenneth Murray, who felt that teaching Western academic approaches would undermine the authenticity of indigenous arts and crafts, Onabolu educated a large number of Nigerian artists.

Ben Enwonwu, a pupil of Murray who subsequently attended the Slade School of Art in London, was the first significant modernist artist in Nigeria.

He returned in 1947 and was appointed art adviser to the colonial government. Colonial art instruction was frequently attacked by Enwonwu for neglecting African themes.

He frequently drew on African themes, such as dance and masks, even though his approach varied from realistic figures to abstraction.

Demas Nwoko, and Bruce Onobrakpeya, this group was inspired by Pan-Africanism and the cultural pride championed by political leaders like Nnamdi Azikiwe and Kwame Nkrumah.

Rather than fixating on one national style, these artists explored local traditions in new ways Okeke used the Igbo body and mural art style Uli in his paintings, and Nwoko created terracotta sculptures reminiscent of ancient Nok figures.

While they concentrated on African themes, other Nigerian modernists of the 1960s, such as Jimo Akolo, Erhabor Emokpae, and Okpu Eze, also developed expressionist and surrealist styles influenced by older European modernists.

The Art Society’s focus on native styles contrasted with their more global perspective. Artists schooled in workshops led by German critic Ulli Beier and affiliated with the Mbari-Mbayo Club in Osogbo, on the other hand, concentrated on Yoruba subjects.

Beier also backed the Zaria group early on. The colonial presence of French artists in Dakar had little long-term impact in Senegal.

Only after gaining independence in 1960, under the leadership of President Léopold Sédar Senghor, did a truly modern art movement emerge.

Only after gaining independence in 1960, under the leadership of President Léopold Sédar Senghor, did a truly modern art movement emerge. Senghor, a prominent Negritude poet and theorist, favored contemporary art that honored black identity and culture.

He established official art support networks, museums, and educational institutions. Along with French artist Pierre Lods, the government employed Papa Ibra Tall and Iba N’Diaye to lead the visual arts divisions at the recently established Ecole des Arts in Dakar.

In keeping with Senghor’s Negritude, Tall and his students produced paintings and tapestries that were replete with black heritage-inspired symbols and rhythmic lines.

Based on the notion of African ingenuity, Lods promoted untrained artistic expression. The School of Dakar is the name given to their work.

N’Diaye’s fine arts department, on the other hand, opposed the notion that Senegalese art should serve racial or national identity by promoting technical mastery and individual expression.

N’Diaye arranged an exhibition of the School of Dakar for the 1966 First World Festival of Negro Arts in Dakar, even though he disagreed with the ideology that underpinned it.

Even while some artists, like N’Diaye, opposed this focus, Senegal’s 1960s modern art was strongly linked to Negritude themes due to official sponsorship, especially for Lods’s and Tall’s efforts.

(iii) East Africa

Ethiopia held an important position in East Africa due to its lack of colonization. Christian art had a long history there that continued until the 20th century.

French-trained artists like Egegnehu Engeda and Abebe Wolde Giorgis were the founders of modern art in Ethiopia. They made Ethiopian art more realistic.

Artists from a second generation, like Gebre Kristos Desta, Skunder Boghossian, and Afewerk Tekle, created distinctive styles of their own. Alessk Tekle depicted Christian themes and African customs with vivid colors and realistic styles.

Skunder Boghossian expressed a global black identity by fusing jazz, African spirituality, and surrealism.

In order to convey his individuality and inventiveness, Gebre Kristos Desta eschewed African subjects and concentrated on abstract expressionism.

British colonial schools inspired modern art in nearby East African nations like Tanzania and Uganda. British educator Margaret Trowell began teaching painting at Uganda’s Makerere University.

Sam Ntiro and Elimo Njau, two of her students, depicted African rural life in straightforward and organic ways. Later, European post-Cubist forms were introduced by artists such as Francis Nnaggenda, Jonathan Kingdon, and Cecil Todd.

East African modern art, however, did not adhere to a particular trend or style. It continued to be varied and receptive to various influences, fusing regional customs with international art movements.

(iv) Southern Africa

Christian mission-run studios for art were the origin of modern art in most of Southern Africa, with the exception of South Africa. Teaching people how to make holy art was the primary goal of these missions.

The Cyrene Mission in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), which began in 1939, is a prime example. Reverend Edward Paterson served as its leader and provided art instruction in a laid-back and supportive manner.

Despite their inventiveness, the pupils’ paintings frequently lacked artistic proficiency and instruction, and they primarily depicted Christian themes.

At this early stage, the topics and techniques of Southern African modern art were limited. Due to its religious origins, it was more concerned with spreading Christian ideas than it was with examining African identity or individual expression.

The lack of formal training and freedom meant that modern art in this region developed slowly compared to other parts of Africa.

Famous African Artists

1. Wangechi Mutu

Although now based in New York, Kenyan artist Wangechi Mutu creates artworks that are both provocative and mesmerizing.

Associated with the Afro-futurist movement, her work blends African cultural symbolism with science fiction elements, resulting in surreal and often unsettling characters that challenge perceptions of beauty, identity, and power.

2. El Anatsui

El Anatsui, a renowned Ghanaian sculptor, gained international acclaim for his monumental installations crafted from thousands of recycled bottle caps.

These shimmering, fabric-like sculptures have adorned walls of prestigious institutions, including the Venice Arsenale and Berlin’s Alte National Gallery, transforming waste into powerful visual statements on consumption, transformation, and memory.

3. Thandiwe Muriu

Thandiwe Muriu is a rising star from Kenya, known for her striking fashion-inspired photography. Her vibrant portraits combine traditional African textiles with contemporary aesthetics, often featuring Black models with natural afro hairstyles.

Her work is a celebration of African beauty, culture, and identity, with each image echoing themes of empowerment and heritage.

4. William Kentridge

South African artist William Kentridge is celebrated for his powerful charcoal drawings and animated films.

Deeply influenced by the legacy of apartheid, Kentridge’s work is both political and poetic, capturing the complexities of history, memory, and identity through layered imagery and motion.

5. Julie Mehretu

Julie Mehretu is a Ethiopian-American artist known for her large-scale, layered paintings that combine maps, architectural plans, and gestural marks.

Her abstract compositions speak to themes of migration, geopolitics, and displacement, creating visual spaces that are both chaotic and deeply structured.

Mehretu’s work offers a global and conceptual perspective on African identity in contemporary art.

African Art Movements

Tradition, symbolism, and cultural expression are the basis of African art’s long and varied past.

African artists were already developing distinctive styles that emphasized detachment, stylized shapes, and spiritual meaning prior to the emergence of modern Western art movements.

They produced sculptures, masks, fabrics, and wood carvings that were frequently used in ceremonies and rituals.

Despite not being initially classified as “art” in the Western sense, these traditional forms had a big impact on important 20th-century European art movements.

Cubism

Cubism was one of the most famous movements that drew inspiration from African art. African masks and statues served as a major source of influence for artists such as Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque.

Their significant departure from conventional Western approaches was prompted by the striking, abstract shapes and fractured perspectives they observed in African art.

Picasso is renowned for attributing his understanding of how to transcend realism and investigate novel kinds of visual language to African masks.

His early Cubist pieces, such Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, are blatant examples of this influence.

Expressionism

Another Western trend that drew inspiration from African art was expressionism. Expressionist painters prioritized inner experience and unfiltered emotion over accurate portrayal.

African masks and sculptures, which frequently featured exaggerated features and non-naturalistic forms, were appreciated for their intensity and spiritual potency.

By employing bold lines and distortion to appeal to more profound human emotions, Expressionists were able to depict intense emotional states.

Fauvism

African art also influenced Fauvism, a movement renowned for its vivid hues and straightforward shapes.

African textiles and motifs captivated artists such as Henri Matisse. The so-called “wild beasts” of the Fauves were known for their impulsive brushwork and strong, flat colors.

African art, with its decorative elements and emphasis on design, encouraged them to move away from traditional perspective and embrace more expressive, colorful compositions.

Conclusion

African modernism served as both a critique and a reimagining of global art movements. It gave voice to African nations during their journey toward decolonization and self-definition.

By the 1970s, this powerful wave transitioned into contemporary African art, which adopted a more global outlook while moving beyond the nationalistic focus of earlier decades.

Yet, the legacy of African modernism endures as a testimony to resilience, identity, and the creativity that reshaped modern art through an African lens.

FAQ’s

It blends traditional African elements with modern techniques to express identity, independence, and social change.

Modernist artwork breaks away from traditional forms, emphasizing innovation, abstraction, and the artist’s personal vision.

African art inspired Western modernists like Picasso and Matisse with its abstract forms, bold lines, and spiritual symbolism.

African art is a diverse and symbolic expression rooted in cultural traditions, spirituality, community, and everyday life.

Related Posts

Qrederick Buechner Quotes | Writing Style